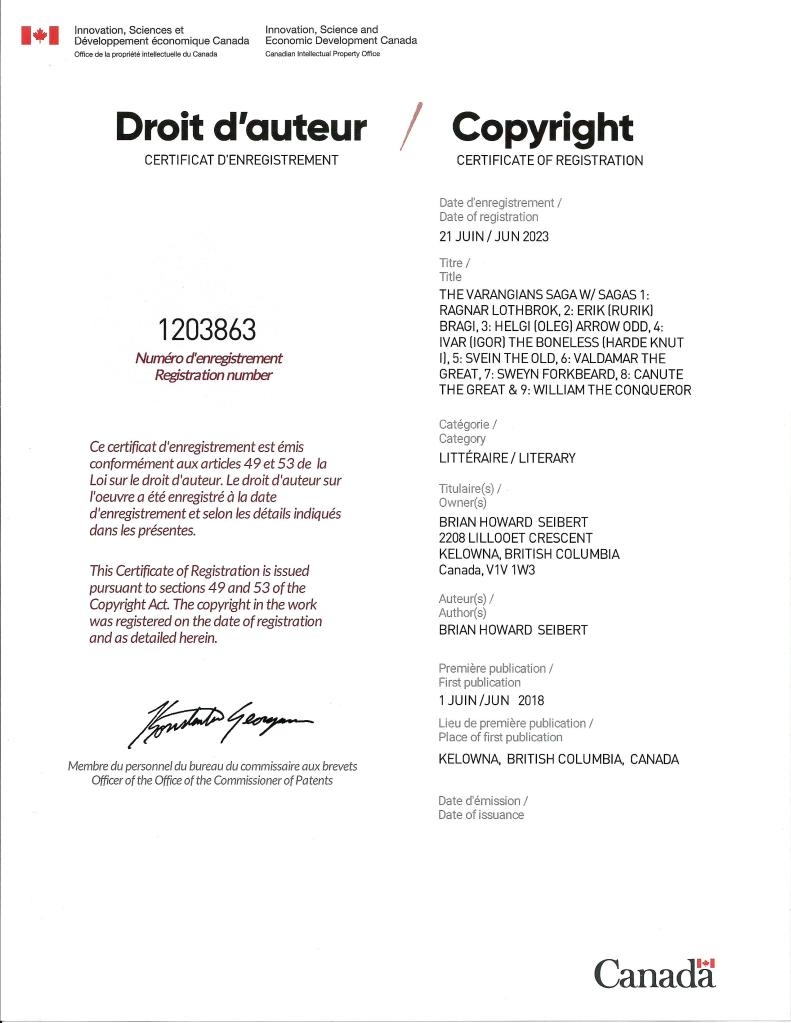

THE VARANGIANS SAGA SERIES COPYRIGHT CERTIFICATE OF REGISTRATION Has Been Added to The Site Under the New Heading The VARANGIANS / UKRAINIANS Book Series – The True History of ‘The Great Viking Manifestation of Medieval Europe’© and the below Post Covers The Literary Copyright Certificate and further Intellectual Property claims as follows:

THE VARANGIANS / UKRAINIANS SAGA SERIES

A Copyrighted Literary Work By

Brian Howard Seibert

© Copyright by Brian Howard Seibert

The title of the Copyrighted Literary Work ‘The VARANGIANS Saga Series’ was maximized to include the short form titles of the related Sagas included (but not limited) in the work as follows:

BOOK ONE: The Saga of King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson (Circa 800 – 822 CE)

BOOK TWO: The Saga of Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson (Circa 828 – 841 CE)

BOOK THREE: The Saga of Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ Erikson (Circa 839 – 912 CE)

BOOK FOUR: The Saga of Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson (Circa 896 – 945 CE)

BOOK FIVE: The Saga of Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson (Circa 943 – 976 CE)

BOOK SIX: The Saga of Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ Sveinson (Circa 968 – 990 CE)

BOOK SEVEN: The Saga of King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson (Circa 986 – 1014 CE)

BOOK EIGHT: The Saga of King Canute ‘the Great’ Sweynson (Circa 1014 – 1035 CE)

BOOK NINE: The Saga of King William ‘the Conqueror’ Robertson (Circa 1036 – 1066+CE)

With Copyrighted Intellectual Property in the Work By

Brian Howard Seibert

© Copyright by Brian Howard Seibert

The Copyrighted Intellectual Property of the Work ‘The VARANGIANS Saga Series’ includes (but is not limited to) the following series of related ideas:

As well as making claim to a Literary Copyright, I, Brian Howard Seibert, lay claim to an Intellectual Property Copyright on a series of discoveries/ideas based upon four decades of research and evaluation that concludes that it was Danish kings and princes who founded what has come to be known as the Kievan Rus’ state with intellectual claims as follows:

BOOK ONE: The Saga of King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson is based upon Book Nine of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Saga of the Volsungs. Because Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ is the earliest and most legendary of the Hraes’ kings and princes, I waited until I had completed Book 8 before attempting Book 1 and, as Saxo, himself, saved Ragnar to the last of his Nine Books of Danish History, I am guessing he did the same for similar reasons. I am glad I waited, but many of my Book 1 theories remain from very early on in the research process and from them I hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

1.1 That the famed shield called “Hrae’s Ship’s Round” mentioned in the Elder Edda was the shield that ‘Hrae’ Gunnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson took shelter under while attacking the Greek fire Breathing Byzantine bireme, Fafnir, and that the Hrae prename came from the roar of the pneumatically propelled Greek fire emulsion flame that flew from the firetube of the bireme.

“And his shield was called ‘Hrae’s Ship’s Round’,

And his followers were called the Hraes’.”

Eyvinder Skald-Despoiler; Skaldskaparmal

1.2 That the Rus’ were called ‘Dromitai’ by the Romans, meaning ‘men who run fast’, as an insult for the Rus’ retreat back up the riverways of Rus’ before the much larger army of the Khazars (Huns) in Saxo’s Book 5. This ‘men who run fast’ insult was continued forward when in 1018 AD Bishop Thietmar of Meresburg called the citizens of Kiev ‘Swift Danes and their Runaway Slavs’ after the Rus’ abandoned Kiev before the armies of the Germans and Poles. It was further carried on into 1040 AD when the English began calling their King Harald, successor of Canute, ‘the Harefoot’, meaning ‘the Swift’ as an insult and not ‘fleet of foot’ as is often surmised.

“These sentences give good sense if we abstract the words Áŋœřȧȿ … ßàþõ, for we then get left with the ordinary aetiological explanation of the two names of the Rus’, ‘Rhos’ and ‘Dromitai’: they are called ‘Rhos’ after the name of a mighty man of valour so called, and ‘Dromitai’ because they can run fast.”

Jenkins, Romilly: Studies on Byzantine History of the 9th and 10th Centuries.

1.3 That the name Varangians comes from Vay, meaning Way, and Range, meaning to Wander, or Way Wanderers. In my early studies I learned that the Rang River in Iceland meant the Wandering River and Vay speaks for itself. Varangers were intially Wanderers of the Nor’Way as can be seen in the Varanger Fjord of the Northern Cape of Norway where the trading fleets gathered to catch the right wind to take them into the White Sea, which was the original Varangian Sea of the Sagas and Chronicles.

1.4 That the name Nor’Way comes from the original Northern Way trade route name for transportation and commerce of goods conducted across Norway’s North Cape and into the White Sea and the riverways of Northern Hraes’.

BOOK TWO: The Saga of Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson is based upon Book Five of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Saga of King Heidrek ‘the Wise’ (aka Hervor’s Saga) by an unknown contemporary author. This was the first discovery. While preparing a University research essay on the origins of the play ‘Hamlet, Prince of Denmark’ by William Shakespeare, I read Books Three and Four of Saxo’s Nine Books of Danish History which contain the Tale of Prince Amleth, a story almost identical to the 16th century play that was compiled by Saxo in the 12th century. Reading on to Book Five of Saxo’s work I found a tale of two Norwegian brothers, Erik and Roller Ragnarson, who join their brother-in-law, King Frodi of Denmark, an Angle king of Jutland, in establishing a trading empire in Scythia that culminates in the famous Battle of the Goths and the Huns and the total victory of the Danes. Having studied Roman History in first year university and Khazar History in second, I came to the conclusion that this tale was about the 9th century entry of Varangians into Scythia and their conquest of Kiev from Khazar domination. In 1984 I set about turning Saxo’s 50 page Book Five History into a 500 page Historical Research Novel to investigate how well Saxo’s work, which he had placed in the time of Christ, would fare in 9th century Kievan Scythia. It did very well, and from it I hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

2.1 That the Ragnar father and Kraka mother characters of the two Norwegian brothers in the saga were none other than King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson and Princess Aslaug ‘Kraka’ Sigurd-Fafnirsbanesdottir.

2.2 That Erik ‘the Eloquent’ Ragnarson was also known as King Heidrek ‘the Wise’ and Prince Rurik of Novgorod and perhaps Prince Rorik of Jutland.

2.3 That King Roller Ragnarson of Norway later became Duke Rollo of Normandy.

2.4 That the three brothers of Saxo’s Book 5, Erik, Roller and Frodi were the founding Varangian brothers, Rurik, Truvor and Sineus mentioned in the Russian Primary Chronicle.

2.5 That the children of King Frodi by Queen Alfhild, Princess Eyfura and Prince Alf, would play roles in the following two sagas.

2.6 That King Frodi ‘the Peaceful’ Fridleifson had assumed the Khazar title of Kagan of Kiev after taking the city from the Huns and that his brother-in-law, Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson, had assumed the title of Kagan-Bek.

“…along with his envoys the Emperor sent also some men who called themselves and their own people Rhos; they asserted that their king, Chacanus by name, had sent them to Theophilos to establish amity.”

Prudentius, Bishop of Troyes; Annales Bertiniani (839 AD)

BOOK THREE: The Saga of Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ Erikson is based upon Book Five of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Saga of Arrow Odd by an unknown contemporary author. Prince Helgi (Oleg) of Kiev (ruled c. 879-912) of the Chronicle corresponds with Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ Erikson, of ‘Arrow Odd’s Saga’ fame, and was the bane of King Frodi and then his son, King Alf of Kiev. Prince Helgi (Oleg) ruled Kiev until his death from the poisonous bite of a snake that struck out from under the skull of a horse he had owned just after he had given it a kick, the same death that Arrow-Odd experiences in the Norse Saga. In the book I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

3.1 That King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’s death by poisonous snake bites was derived from the kenning for death by cuts of poisonous blood-snakes (swords) by twelve swordsmen so that no one person could be blamed for the death of the most famous Viking.

3.2 That Prince Helgi (Oleg) ‘Arrow Odd’s death by poisonous snake bite was derived from the kenning of death by a poisonous blood-snake (sword) under the skull of Faxi (the skull above the bow of the longship ‘Fair Faxi’.

3.3 That Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ was the sea cow that killed King Frodi in Kiev because King Frodi had targeted Prince Helgi for death to avenge Helgi’s killing of Frodi’s twelve grandsons at the Holmganger on Samso.

3.4 That Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ killed King Frodi’s son and successor, King Alf ‘Bjalki’, in Kiev because he had refused to pay tithes to King Olmar of Tmutorokan.

3.5 That in the battle against Alf ‘Bjalki’ much witchcraft was used that is very similar to the witchcraft later used in the Battle of Hjorungavagr, namely the five arrows of death used by the spirit of Thorgerder Helgibruder and of Goddess Irpa.

BOOK FOUR: The Saga of Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson is based upon Book Six of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The History of Leo ‘the Deacon’ by Leo ‘the Deacon’ of Constantinople, a contemporary author. Prince Eyfur (grandson of King Frodi) aka Ivar (Igor) of Kiev (ruled c. 912-945) of the Chronicle, corresponds with King Fridleif of Book Six of Saxo’s History and is also likely King Harde Knute I, who appears in Denmark for a twenty year period that corresponds with a twenty year lacuna in the Chronicle’s history. His descendants form a whole line of Danish kings called the Knotlings. In the book I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

4.1 That Prince Ivar (Igor) of Kiev was Ivar ‘the Boneless’ of Scandinavian Sagas.

“Erik ‘Bragi’ came to me in a dream and he said, ‘Ivar the Boneless is Prince Igor of Kiev’, so I researched Ivar the Boneless. It was said in the Sagas that he had no bones in his legs. Then I researched Prince Igor of Kiev, hoping to find a similar nickname, but I could find none.

‘Show me,’ I pleaded with Erik. ‘Show me.’ He came to me in a dream again and repeated ‘Ivar the Boneless IS Prince Igor of Kiev.’ So I researched further and read The History of Leo ‘the Deacon’ and Leo relates how Emperor John Tzimiskes tells Ivar’s son Svein what had happened to his father: ‘on his campaign against the Germans, he was captured by them, tied to tree trunks, and torn in two.’

But Prince Erik said, ‘Prince Igor of Kiev IS Ivar the Boneless.’ Perhaps he did not die from this Roman form of execution. The Sagas also said he fought while borne into battle upon a shield so perhaps he was maimed by the attack. But even if he did die, he still would have been called ‘the Boneless’ post-mortem anyway. It was the Viking way.”

Comments: ‘The History of Leo ‘the Deacon’ as read by BH Seibert

4.2 That Prince Ivar (Igor) of Kiev was the son of Princess Eyfura Frodisdottir and may have originally been named Eyfur, the masculine form of Eyfura (meaning Island Fir or Pine). His father may have been Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson with Ivar once again tying the royal lines of ‘the Old Fridleif-Frodi Line of Anglish Danish kings’ with the Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson Line of Norwegian Danish kings. Eyfur was an uncommon name and Ivar and sometimes Ingvar was used with Igor being the Slavic form of the name.

4.3 That Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson (and Eyfurason) of Kiev returned to Denmark as King Harde Knute I. Solely from a point of ‘Due Diligence’, I checked Danish History to see if a new Danish king had happened to turn up during a twenty year lacuna in the story of Prince Ivar (Igor) of Kiev in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle between the years 916 and 936 AD and, unexpectedly, an unknown king had shown up! A King Harde Knut I of Denmark reigned from circa 915 AD for about thirty years according to Adam of Bremen, a contemporary historian, so, to about 945 AD, which is the year the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle tells us that Prince Ivar (Igor) of Kiev died! But Prince Igor reappears in the Hraes’ chronicle in 936, so it is possible that he ruled both lands.

The name ‘Harde Knut’ in Danish means ‘Hard Knot’, and I expostulated that it was a hard knot indeed that took the legs of our young prince. Harde Knut ‘the First’ was the start of a long line of Knot Kings or Knytlings, starting with several Canutes, Knuts, Knuds and many more Harde Knuts, all stemming from one of the most famous of Vikings, Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’. There were no Knuts of any kind before him, but many after, and the preponderance of evidence continues to grow. King Harde Knut’s son in Denmark was King Gorm ‘the Old’, Gorm meaning worm or Snake and ‘the Old’ from the ‘Old’ Fridleif-Frodi line of Anglish Danish kings. His son in the east, as Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’, was Prince Svein ‘the Old’, or Sveinald, with Svein meaning Swine and, again, ‘Old’ of the Fridleif-Frodi line. A storm is brewing here, the Swine being a mortal enemy of the Snake, the ‘Snake’-King AElla of York having taken the life of ‘the Old Boar’, King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’, and Gorm’s byname being ‘ the Englishman’, perhaps signifying his mother was an English princess from York, perhaps Princess Blyia, granddaughter of AElla. In the novel we explore the most famous death of Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ and the vengeances that were unleashed upon AElla and his line.

4.4 That Prince Fridleif ‘Hiarnsbane’ Frodeson of Book Six of Saxo’s Danish History was Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson (and Eyfurason) and he returned to Denmark from Hraes’ and killed the elected King Hiarn of Denmark and reclaimed his grandfather’s throne as king of the Anglish Danes of Jutland.

BOOK FIVE: The Saga of Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson is based upon Book Six of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Hraes’ Primary Chronicle. Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson or Sveinald (Sviatoslav) of Kiev (ruled c. 945-972) of the Chronicle corresponds to King Frodi of Book Six of Saxo’s History. This Svein is Sviatoslav ‘the Brave’ who almost defeated the whole Eastern Roman Empire before getting himself booted out of Rus’ in favour of his three sons, Yaropolk (Ivar), Oleg (Helgi) and Vladimir (Valdamar). Prince Svein returns to Denmark as King Sweyn Forkbeard and culminates his career by conquering England on Christmas Day of 1013 before being poisoned 5 weeks later. The second Hraes’ prince to come from Kiev to take his place as a Danish king was Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson, or Sveinald, who took the throne from his nephew, King Harald ‘Bluetooth’ Gormson, son of King Gorm ‘the Old’ Knut/Ivarson after his victory at the Battle of Hjorungavagr. In this Book 5 I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

5.1 That Prince Svein (Slavic: Sviatoslav) did not die in the 972 AD attack of Pechenegs at the Ford of Vrar as told in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle, as the tale of his skull being turned into a cup was a Roman fiction lifted from the death of Roman Emperor Nicephorus ‘the First’ a hundred years earlier, who had his skull turned into a cup by Khan Krum of Bulgaria. Prince Sviatoslav’s General Sveinald, who escaped the battle and made his way to Kiev, was actually Prince Sveinald himself and he did make it to Kiev to celebrate the gifted survival of his earlier Battle of Dorostolon against Emperor John Tzimiskes of Rome.

5.2 That Prince Svein left Hraes’ to his three sons, Ivar, Helgi and Valdamar, and went to Denmark and met with Harald ‘Bluetooth’ and then left for Norway with Jarl Haakon Sigurdsson, where he was adopted by the jarl and befriended by his son Eirik.

5.3 That Prince Svein was also known as Gold Harald because he was quite rich when compared against his nephew, King Harald ‘Bluetooth’, who was historically lacking in wealth.

5.4 That Prince Svein was victorious at the famed Battle of Hjorungavagr and that he pursued and drove King Harald ‘Bluetooth’ out of Roskilde and took his court as King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson of Denmark.

5.5 That Prince Svein/King Sweyn is also portrayed as King Frodi, the second king in Book Six of Saxo’s Danish History.

BOOK SIX: The Saga of Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ Sveinson is based upon Book Six of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Hraes’ Primary Chronicle. Prince Valdamar (Vladimir) ‘the Great’ of Kiev (ruled c. 980-1015) of the Chronicle, corresponds with King Ingjald of Book Six of Saxo’s History and would, years later, return to the west as King Canute ‘the Great’ of England, Denmark and Norway, (ruled c. 1016-1035) after the death of his father, King Sweyn Forkbeard of England. Coincidentally, just as his great great grandfather King Frodi had married a Khazar princess to gain the title Kagan, so too did Prince Valdamar of Kiev marry the Roman Princess Anna Porphyrogennetos (meaning born of the purple) to gain the title of Czar (Caesar) for all his subsequent offspring in Russia. In this Book 6 I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

6.1 That Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ of Kiev corresponds with the third royal, King Ingjald of Book Six of Saxo’s Danish History and would, years later, return to the west as King Canute ‘the Great’ of England, Denmark and Norway. The wanton profligacy of both characters matches unmistakably.

6.2 That when young Prince Valdamar fled to the Varangians to escape the wrath of his older brother Ivar, who had just killed their middle brother Helgi, he sought sanctuary with Jarl Haakon of Lade in Norway and with Prince Svein, his father, who was living there. They returned to Hraes’ with a Norwegian army and the two Varangians who killed Prince Ivar for his fratricide were none other than Prince Svein and Jarl Eirik Haakonsson (Blud).

6.3 That Prince Valdamar (Slavic: Vladimir) did not die of disease in 1015 AD as told in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle, as the tale of his body being rolled up in a carpet and lowered down a floor was a Roman fiction lifted from the death of Roman Emperor Nicephorus ‘the Second’ a few decades earlier, when he was murdered by John Tzimiskes in his palace in Constantinople. This same Roman tale is carried on into the deaths of Princes Boris and Gleb and their manservant who was beheaded after death, as was Emperor Nicephorus.

BOOK SEVEN: The Saga of King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson is based upon The Saga of the Jomsvikings and upon The Anglo Saxon Chronicle. In this Book 7 I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

7.1 That King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ waged a decades long series of raids against England for both wealth and slaves to feed his Hraes’ trade routes through Scythia to Constantinople and Baghdad.

7.2 That King Sweyn’s slave trading business was partially responsible for the enslavement of Prince Olaf Tryggvason and led to the later Christianization of Olaf in England and the resulting conflicts between the two royals when Olaf became the Christian King of Norway, likely with English support.

7.3 That King Athelred ‘the Unready’ of England ordered the Saint Brice’s Day massacre of Danes in 1002 AD in retribution against King Sweyn for his slaying of King Olaf at the Battle of the Svold in 1000 AD.

7.4 That the massacre led to an outright war between the Danes of Denmark, Hraes’ and Normandy and the Saxons of England. King Sweyn was helped in this decade long war by his son, Grand Prince Valdamar (Vladimir) ‘the Great’ of Kiev, which may help account for the paucity of events in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle on the rule of Prince Vladimir in this period. King Sweyn forced King Athelred out of England and took his throne Christmas Day of 1013 AD, but was dead, likely poisoned, by February of 1014 AD. His son, Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ was elected King of England after his father’s death, but King Athelred returned from exile in Normandy and the English rose up in revolt and drove Prince Valdamar out of England.

7.5 That Prince Valdamar fled with his fleet, but stopped on the Isle of Sandwich on his way south east and maimed 200 hostages that his father had taken over the years and left them on the sands of Sandwich. By royal rights he could have slain them all there but he did not, because even in Kiev, after becoming a Christian, he would no longer execute capital criminals for fear of God’s retribution in the afterlife. Also, Prince Valdamar’s maimings were selectively deliberate, as the Hraes’ had always retrained their own maimed warriors for other military tasks and Valdy had future plans for his maimed hostages when he returned from Hraes’ to retake England.

7.6 That during this period of decades long strife with the English, King Sweyn financed his wars with profits from fur and slave trading through the riverways of Hraes’ and that this terrible trade had always fully financed ‘The Great Viking Manifestation of the Middle Ages’.

7.7 That the Hraes’ Danes of Denmark had begun direct sailings to the Newfoundland and had extended their vast trading network up the Kanata (Canada) River (St. Laurence) and into the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi River which was soon to become the Valley of the Mound Builders.

7.8 That Chapter 13 of Erik ‘the Red’s Saga describes the Hraes’ Cavalry Legion of the One Footers, soldiers that had lost a leg in battle and had been trained to become cavalry officers, as follows:

“One morning Karlsefni’s people beheld as it were a glittering speak above the open space in front of them, and they shouted at it. It stirred itself, and it was a being of the race of men that have only one foot, and he came down quickly to where they lay. Thorvald, son of Eirik the Red, sat at the tiller, and the One-footer shot him with an arrow in the lower abdomen.”

“Then they journeyed away back again northwards, and saw, as they thought, the land of the One-footers. They wished, however, no longer to risk their company.”

“Now, when they sailed from Vinland, they had a southern wind, and reached Markland, and found five Skrœlingar; one was a bearded man, two were women, two children. Karlsefni’s people caught the children, but the others escaped and sunk down into the earth. And they took the children with them, and taught them their speech, and they were baptized. The children called their mother Vœtilldi, and their father Uvœgi. They said that kings ruled over the land of the Skrœlingar, one of whom was called Avalldamon, and the other Valldidida. They said also that there were no houses, and the people lived in caves or holes. They said, moreover, that there was a land on the other side over against their land, and the people there were dressed in white garments, uttered loud cries, bore long poles, and wore fringes. This was supposed to be Hvitramannaland (whiteman’s land). Then came they to Greenland, and remained with Eirik the Red during the winter.”

The above caves or holes are apt descriptions of the longhalls reconstructed at L’Anse Aux Meadows, the Viking settlement in Newfoundland. The men in white garments bearing long poles and wearing fringes are knights. The above descriptions have been in Erik ‘the Red’s Saga for over a thousand years and people still don’t get it? Learn your history or you are doomed to repeat it!

BOOK EIGHT: The Saga of King Canute ‘the Great’ Sweynson is based upon Book Ten of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus and upon The Anglo Saxon Chronicle.

In this Book 8 I have hypothesized the following intellectual property discoveries:

8.1 That King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson of Denmark was helped in his decade long war against the Saxons of England by his son, Grand Prince Valdamar (Vladimir) ‘the Great’ Sveinson of Kiev, which may help account for the paucity of events in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle on the rule of Prince Vladimir in this period. King Sweyn forced King Athelred out of England and took his throne Christmas Day of 1013 AD, but was dead, likely poisoned, by February of 1014 AD. His son, Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ was elected King of England after his father’s death, but King Athelred returned from exile in Normandy and the English rose up in revolt and drove Prince Valdamar out of England and back to Kievan Hraes’, which he had already given over to his many sons to rule.

8.2 That Prince Valdamar planned to continue his father’s war against the Saxons of England, financing his war with profits from fur and slave trading through the riverways of Hraes’ and with gold that was being obtained through trade the Hraes’ Danes of Denmark and Kiev had begun earning through direct sailings for trade in the Newfoundland, extending their vast trading network up the Kanata (Canada) River (St. Laurence) and into the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi River and the Valley of the Mound Builders.

8.3 That Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ changed his title and name to King Canute ‘the Great’ to facilitate his acceptance as king by the English as a new Latin Christian convert versus his former Orthodox Christian faith because the Great Schism between Latin and Orthodox Christianity was growing exponentially.

8.4 That in late 1014 AD Prince Valdamar returned to Hraes’ to raise an army to facilitate his reconquest of England and in January of 1016 AD he led this army south through Hraes’ where his Black Sea fleet was augmented by Roman bireme ships loaned him by his brother-in-law, Emperor Basil of Constantinople, and that, for this favour, Prince Valdamar trained his army by attacking Khazars in Scythia for the Romans. Valdy needed these large ships to defeat the new English ships (Cogs) that had been built to defeat Viking longships quite effectively.

8.5 That Prince Valdamar’s eldest son, Prince Svein (Slavic: Boarus), left Kiev in the hands of his brother, Prince Sviatopolk, and helped his father raise said army and then led them south, not against Pechenegs as described in the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle, but against said Khazars and that he was assisted in this by his adopted brother, Prince Godwin of Sussex (Slavic: Gleb), who had come with Prince Valdamar in his retreat from England. Saints Boris and Gleb of Kievan Rus’ are likely Prince Sveinald of Kiev, grandson of King Sweyn, and Prince Godwin, son of Wolfnoth Cild of Sussex:

From Wiki: Gleb (Ukrainian: Гліб) is a Slavic male given name derived from the Old Norse name Guðleifr, which means “heir of god.” It is popular in Ukraine due to an early martyr, Saint Gleb, who is venerated by Eastern Orthodox churches and is the Ukrainian form of the Old Norse name Guðleifr, which was derived from the elements guð “god” and leif “inheritance, legacy”.

From Wiki: Godwin was born c. 1001, likely in Sussex. Godwin’s father was probably Wulfnoth Cild, who was a thegn of Sussex. His origin is unknown but ‘Child’ (also written Cild) is cognate with ‘the Younger’ or ‘Junior’ and is today associated with some form of inheritance. In 1009 Wulfnoth was accused of unknown crimes at a muster of Æthelred the Unready’s fleet and fled with twenty ships [the new larger and taller ships]; the ships sent to pursue him were destroyed in a storm.

From The Rus’ Primary Chronicle 1953: 119, 250 n103 and Franklin and Shepard 1996: 200):

“The Byzantine historian John Skylitzes tells of a certain Sphengos, prince of the Rus, who cooperated with a Byzantine naval expedition against ‘Khazaria’ in [January of] 1016. ‘Sphengos’ is probably a Greek enunciation of a Scandinavian name such as Svein or Sveinki. At around the same time Mstislav himself is reported to have subjugated the Kasogians (the Adyge of the Kuban region and northern Caucasus)”.

8.6 That Prince Sveinald ‘Boarus’ Valdamarson returned to Hraes’ from helping his father in his war on England and was slain by his brother, Sviatopolk, who did not want to give up his throne in Kiev. Prince Godwin ‘Gleb’ Wulfnothson of Sussex seems to have returned with him and is said to have also been slain, but this is likely false, as Godwin survived. The writers of the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle continue killing off every prince that leaves Rus’. Even the evil Prince Sviatopolk is killed off as he is driven out of Rus’ by Prince Yaroslav. His bones supposedly grow soft as he rides to Hungary and sanctuary, but the disease kills him of course. Perhaps he was struck down by the same disease that set upon Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’.

8.7 That Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’, having returned to England as King Canute ‘the Great’, defeated King Edmund Athelredson at the Battle of Assandun on October 18, 1016 AD, and though agreeing to share the kingdom, Canute captured Edmund five weeks later in a siege (that included the war crime of crossbow slaying of defecating soldiers) and sent Edmund and 800 of his retainers, including at least two of his sons, as prisoners back to Kievan Hraes’.

8.8 That in 1018 AD King Boleslaw of Poland, with German assistance, attacked Kiev, possibly in an effort to free King Edmund, and that Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg described the Kievan Hraes’ populace of that time as being ‘Swift Danes’ and their ‘Runaway Slaves’ (meaning Slavs) and that this description is meant to be an insult to the Danish rulers of Kiev by the historian in that it refers to the Roman reference to the Hraes’ two centuries earlier as Dromitai, ‘those who run fast’, as in ‘run from battle’. Prince Ivaraslav (Yaroslav) Valdamarson and his Danes fled Kiev before the attack for the safety of Novgorod according to the Hraes’ Primary Chronicle. The ‘Swift Danes’ insult is carried forward to Valdamar’s son, King Harald ‘Harefoot’ Canuteson, of England, the Harefoot meaning ‘one who flees fast’ and not the ‘fleet of foot’ as it is often interpreted. King Edmund and his retainers had already been sent on to serve in the Varangian Guard of Emperor Basil in Constantinople, but King Boleslaw did seem to have saved two of Edmund’s sons, Edmund Junior and Edward ‘the Exile’, as they were rescued and sent to safety in the Hungarian royal court that Prince Sviatopolk later fled to.

8.9 That in 1024 AD, according to the contemporary Roman History of John Skylitzes, King Edmund may have attempted to escape from service in Constantinople with his retainers and return to England, when it was recorded that a relative of Vladimir’s named Chrysocheir, meaning Gold Hand or Edmund, with a company of 800 men were slaughtered after refusing to lay down their arms in Constantinople. It must be remembered that later, King Harald ‘Hardruler’ Sigurdsson of Norway was also sent into exile in Kievan Hraes’ and then the Varangian Guard in Constantinople from which he escaped successfully. Here is historian Alex Feldman’s interpretation of the event:

FROM ROSSICA ANTIQUA 2018, The First Christian Rus’ Generation:

Contextualizing the Black Sea Events of 1016, 1024 and 1043 by Alex Feldman

The same can be said for another episode mentioned exclusively by Skylitzēs, dating to 1024, when a squadron of Rus’ allegedly attacked imperial positions south of Constantinople (Skylitzes Ioannis 1973: 368 [16:46]8). In Wortley’s translation (Skylitzes Ioannis 2010: 347):

“Anna, the emperor’s sister, died in Russia, predeceased by Vladimir, her husband. Then a man named Chrysocheir, a relative of his, embarked a company of eight hundred men and came to Constantinople, ostensibly to serve as mercenaries. The emperor ordered him to lay down his arms and then he would receive him but [the Russian] was unwilling to do this and sailed through the Propontis. When he came to Abydos he gave battle to the commander there whose duty was to protect the shores and easily defeated him. He passed on to Lemnos where, beguiled by offers of peace, they were all slaughtered by the navy of the Kibyrrhaiote [theme], the commander of Samos, David of Ochrid, and the duke of Thessalonike, Nikephoros Kabasilas”. Wortley claims in a corresponding footnote that “this episode reveals how the Varangian guard was replenished.” While this supposition seems fair, due to this episode’s appearance in this source alone, I would be cautious to assign too much weight to any given theory, such as that of Blöndal and Benedikz (Blöndal, Benedikz 1978: 50), for example, who propose that the name of the Rus’ leader itself, Chrysocheir, could be read as Eadmund, and therefore tie “English noblemen” to Kiev as early as the first quarter of the 11th century.

From Wiki:

‘In the view of M. K. Lawson, the intensity of Edmund’s struggle against the Danes in 1016 is only matched by Alfred the Great’s in 871, and contrasts with Æthelred’s failure. Edmund’s success in raising one army after another suggests that there was little wrong with the organs of government under competent leadership. He was “probably a highly determined, skilled and indeed inspiring leader of men”. Cnut visited his tomb on the anniversary of his death and laid a cloak decorated with peacocks on it to assist in his salvation, peacocks symbolising resurrection.’

King Canute may have exiled King Edmund to the east until he got his Great Northern Empire established, planning to resurrect King Edmund in Wessex as one of the kings under Emperor Canute’s command. Valdamar would need legitimate kings subject to him if he was to be seriously considered as a true Emperor or Caesar to compete with the Czar title that his son, Ivaraslav (Yaroslav) carried by blood.

BOOK NINE: The Saga of King William ‘the Conqueror’ Robertson is based upon TBA.

To be Continued…

Note: This website is about Vikings and Varangians and the way they lived over a thousand years ago. The content is as explicit as Vikings of that time were and scenes of violence and sexuality are depicted without reservation or apology. Reader discretion is advised.

BOOK ONE: The Saga of King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson (Circa 800 – 822 CE)

BOOK ONE: King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ Sigurdson’s third wife, Princess Aslaug, was a young survivor of the Saga of the Volsungs and was a daughter of King Sigurd ‘the Dragon-Slayer’ Fafnirsbane, so this is where Ragnar’s story begins in almost all the ancient tales (except Saxo’s). In our series, we explore this tail end of the Volsungs Saga because King Sigurd appears to be the first ‘Dragon-Slayer’ and King Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ would seem to be the second so, it is a good opportunity to postulate the origins of Fire Breathing Dragons and how they were slain. King Ragnar would lose his Zealand Denmark to the Anglish Danes of Jutland, who spoke Anglish, as did the majority of Vikings who attacked England, where both Anglish and Saxon languages were spoken, sometimes mistakenly called a common Anglo-Saxon language. The Angles and Saxons of England never really did get along, as shall be demonstrated in the following books. King Ragnar assuaged the loss of Zealand by taking York or Jorvik, the City of the Boar, in Angleland and Stavanger Fjord in Thule from which he established his Nor’Way trade route into Scythia. Ragnar died quite famously in his ‘City of the Boar’ and he placed a curse on King AElla of Northumbria and his family that was to reverberate down through the ages.

BOOK TWO: The Saga of Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson (Circa 828 – 841 CE)

Book Two of the Nine Book The Varangians and Ukrainians Series places The Saga of Prince Erik ‘Bragi’ Ragnarson from Book Five of The First Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus (c. 1200 AD) about King Frodi ‘the Peaceful’ puts the saga into its proper chronological location in history. In 1984, when I first started work on the book, I placed Prince Erik’s birth at circa 800 CE, but it has since been revised to 810 CE to better reflect the timelines of the following books in the series. Saxo had originally placed the saga at the time of Christ’s birth and later experts have placed the story at about 400 CE to correspond with the arrival of the Huns on the European scene but, when Attila was driven back to Asia, the Huns didn’t just disappear, they joined the Khazar Empire, just north of the Caspian Sea, and helped the Khazars control the western end of the famous Silk Road Trade Route. Princes Erik and Roller, both sons of Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’, sail off to Zealand to avenge their father’s loss, but Erik falls in love with Princess Gunwar, the sister of the Anglish King Frodi of Jutland and, after his successful Battle Upon the Ice, wherein he destroys the House of Westmar, Erik marries Gunwar and both brothers become King Frodi’s foremost men instead, and the story moves on to the founding of Kievan Hraes’ in present day Ukraine and Belarus. The Danes defeat the Khazars in the famous ‘Battle of the Goths and the Huns’ to establish their position as the great Hraes’ trading empire.

BOOK THREE: The Saga of Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ Erikson (Circa 839 – 912 CE)

Book Three, The Saga of Prince Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ Erikson, recreates Arrow Odd’s Saga of circa 1200 AD to illustrate how Arrow Odd was Prince Helgi (Oleg in Slavic) Erikson of Kiev, by showing that their identical deaths from the bite of a snake was more than just coincidence. The book investigates the true death of Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ by poisoned blood-snakes in York or Jorvik, the ‘City of the Boar’, and how his curse of ‘calling his young porkers to avenge the old boar’ sets up a death spiral between swine and snake that lasts for generations. The book then illustrates the famous Battle of the Berserks on Samso, where Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’ and Hjalmar ‘the Brave’ slay the twelve berserk grandsons of King Frodi on the Danish Island of Samso, setting up a death struggle that takes the Great Pagan Army of the Danes from Denmark to ravage Norway and then England and on to Helluland in Saint Brendan’s Newfoundland. A surprise cycle of vengeance manifests itself in the ‘death by snakebite’ of Helgi ‘Arrow Odd’.

BOOK FOUR: The Saga of Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson (Circa 896 – 945 CE)

Book Four, The Saga of Prince Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Erikson, reveals how Ivar ‘the Boneless’ Ragnarson was actually Prince Eyfur or Ivar (Igor in Slavic) Erikson of Kiev and then King Harde Knute ‘the First’ of Denmark. By comparing a twenty year lacuna in the reign of Prince Igor in The Hraes’ Primary Chronicle with a coinciding twenty year appearance of a King Harde Knute (Hard Knot) of Denmark in European Chronicles, Prince Igor’s punishment by sprung trees, which reportedly tore him apart, may have rather just left him a boneless and very angry young king. Loyal Danes claimed, “It was a hard knot indeed that sprung those trees,” but his conquered English subjects, not being quite as polite, called him, Ivar ‘the Boneless’. The book expands on the death curse of Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’ and the calling of ‘his young porkers to avenge the old boar’ when Ivar leaves his first son, King Gorm (Snake) ‘the Old’, to rule in Denmark and his last son, Prince Svein (Swine) ‘the Old’ to rule in Hraes’, further setting up the death spiral between the swine and snake of the ‘Lothbrok’ curse.

BOOK FIVE: The Saga of Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson (Circa 943 – 976 CE)

Book Five, The Saga of Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson, demonstrates how Prince Sveinald (Sviatoslav in Slavic) ‘the Brave’ of Kiev was really Prince Svein ‘the Old’ Ivarson of Kiev, who later moved to Norway and fought to become King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ of Denmark and England. But before being forced out of Russia, the Swine Prince sated his battle lust by crushing the Khazars and then attacking the great great grandfather of Vlad the Impaler in a bloody campaign into the ‘Heart of Darkness’ of Wallachia that seemed to herald the coming of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and included the famed 666 Salute of the Army of the Impalers. The campaign was so mortifying that the fifteen thousand pounds of gold that Emperor John Tzimiskes of Constantinople paid him to attack the Army of the Impalers seemed not nearly enough, so Prince Svein attacked the Eastern Roman Empire itself. He came close to defeating the greatest empire in the world, but lost and was forced to leave Hraes’ to his three sons. He returned to the Nor’Way and spent twelve years rebuilding Ragnar’s old trade route there.

BOOK SIX: The Saga of Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ Sveinson (Circa 968 – 990 CE)

Book Six, The Saga of Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ Sveinson, establishes how Grand Prince Valdamar (Vladimir in Slavic) ‘the Great’ of Kiev, expanded the Hraes’ Empire and his own family Hamingja by marrying 700 wives that he pampered in estates in and around Kiev. Unlike his father, Svein, he came to the aid of a Roman Emperor, leading six thousand picked Varangian cataphracts against Anatolian rebels, and was rewarded with the hand of Princess Anna Porphyrogennetos of Constantinople, a true Roman Princess born of the purple who could trace her bloodline back to Julius and Augustus Caesar. She was called ‘Czarina’, and after her, all Hraes’ Grand Princes were called ‘Czars’ and their offspring were earnestly sought after, matrimonially, by European royalty.

BOOK SEVEN: The Saga of King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson (Circa 986 – 1014 CE)

In The Saga of King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ Ivarson, Prince Svein anonymously takes the name of Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ in Norway and befriends the Jarls of Lade in Trondheim Fjord in Norway as he expands the Nor’Way trade route of his grandfather, Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’. He had come close to defeating the Eastern Roman Empire, and still felt that he was due at least a shared throne in Constantinople. He used the gold from the Nor’Way trade to rebuild his legions and his Hraes’ cataphracts and though his brother, King Gorm ‘the Old’, was dead, his son, Sweyn’s nephew, King Harald ‘Bluetooth’ Gormson had usurped the throne of Denmark and had hired the famed Jomsvikings to attack Prince Sweyn in Norway, setting up the famous Battle of Hjorungavagr in a fjord south of Lade. King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ would emerge from that confrontation and then he would defeat King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway in the Battle of Svolder in 1000 AD, in an engagement precipitated over the hand of Queen Sigrid ‘the Haughty’ of Sweden. Later he attacked England in revenge for the following St. Brice’s Day Massacre of Danes in 1002 AD and he fought a protracted war with the Saxon King Aethelred ‘the Unready’ that could only be described as the harvesting of the English for sale as slaves in Baghdad and Constantinople. With the help of his son, Prince Valdamar of Kiev, and the legions and cataphracts of Hraes’, he conquered England on Christmas Day of 1013, but victory was not kind to him.

BOOK EIGHT: The Saga of King Canute ‘the Great’ Sweynson (Circa 1014 – 1035 CE)

Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ Sveinson of Kiev, who had supported his father, King Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ of Denmark in attacks upon England left his ‘Czar’ sons in charge of Hraes’ and took over as King Valdamar of England, but the Latin Christian English revolted against his eastern name and Orthodox Christian religion and brought King Aethelred back from exile in Normandy and Valdamar had to return to Hraes’ and gather up the legions he had already sent back after his father’s victory. His half brother was ruling in Denmark and his sons were ruling in Hraes’ so, in 1015 AD Grand Prince Valdamar ‘the Great’ of Kiev was written out of Hraes’ history and in 1016 the Latin Christian Prince Canute ‘the Great’ returned to England to reclaim his throne. He defeated Aethelred’s son, King Edmund ‘Ironside’ of England, at the Battle of Assandun to become King Canute ‘the Great’ of England and later King Knute ‘the Great’ of Denmark and Norway as well. But that is just the start of his story and later Danish Christian Kings would call his saga, and the sagas of his forefathers, The Lying Sagas of Denmark, and would set out to destroy them, claiming that, “true Christians will never read these Sagas”.

BOOK NINE: The Saga of King William ‘the Conqueror’ Robertson (Circa 1036 – 1066+CE)

The Third Danish Conquest of Angleland was seen to herald the end of the Great Viking Manifestation of the Middle Ages, but this, of course, was contested by the Vikings who were still in control of it all. Danish Varangians still ruled in Kiev and Danes still ruled the Northern Empire of Canute ‘the Great’, for the Normans were but Danish Vikings that had taken up the French language, and even Greenland and the Newfoundland were under Danish control in a Hraes’ Empire that ran from the Silk Road of Cathay in the east to the Mayan Road of Yucatan in the west. “We are all the children of Ragnar ‘Lothbrok’,” Queen Emma of Normandy often said. Out of sheer spite the Saxons of England took over the Varangian Guard of Constantinople and would continue their fight against the Normans in Southern Italy as mercenaries of the Byzantine Roman Empire. They would lose there as well, when in the Fourth Crusade of 1204, the Norman Danes would sack the City of Constantinople and hold it long enough to stop the Mongol hoards that would crush the City of Kiev. It would be Emperor Baldwin ‘the First’ of Flanders and Constantinople who would defeat the Mongol Mongke Khan in Thrace. But the Mongols would hold Hraes’ for three hundred years and this heralded the end of the Great Viking Manifestation. The Silk Road was dead awaiting Marco Polo for its revival. But the western Mayan Road would continue to operate for another hundred years until another unforeseen disaster struck. Its repercussions would be witnessed by the Spanish conquerors who followed Christopher Columbus a hundred and fifty years later in the Valley of the Mound Builders.

Conclusion:

By recreating the lives of four generations of Hraes’ Ukrainian Princes and exhibiting how each generation, in succession, later ascended to their inherited thrones in Denmark, the author proves the parallels of the dual rules of Hraes’ Ukrainian Princes and Danish Kings to be cumulatively more than just coincidence. And the author proves that the Danish Kings Harde Knute I, Gorm ‘the Old’ and Harald ‘Bluetooth’ Gormson/Sweyn ‘Forkbeard’ were not Stranger Kings, but were Danes of the Old Jelling Skioldung Fridlief/Frodi line of kings who only began their princely careers in Hraes’ and returned to their kingly duties in Denmark with a lot of Byzantine Roman ideas and heavy cavalry and cataphracts.